Turning to Sacred Scriptures, we find the bearing of palm branches to have been one of the principal ways of manifesting joy; and one not only approved but commanded by God at the time of the foundation of the Jewish religion.

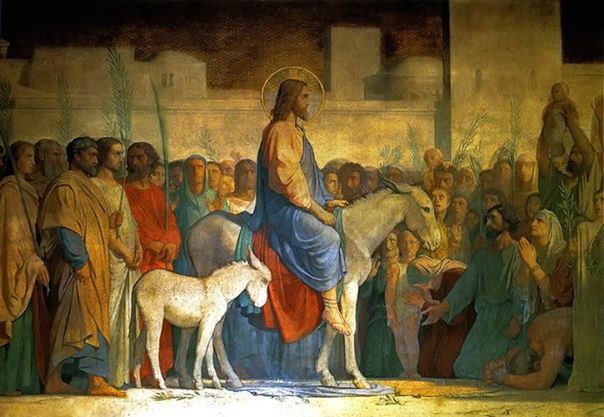

When the people assembled in the fall of the year, after the gathering in the harvest, to celebrate the feast of Tabernacles, God said to them, as we read in Leviticus (xxiii. 40): “You shall take to you on the first day the fruits of the fairest tree, and branches of palm trees, and boughs of thick trees, and willows of the brook; and you shall rejoice before the Lord, you God.” In the Second Book of Machabees (x. 7) it is related that, after the temple was purified from the defilements to which it had been subjected by the enemies of God’s people, the Jews rejoiced as they had formerly been accustomed to do on the feast of Tabernacles; and “therefore they now carried boughs and green branches and palms for Him that had given them good success in cleansing His place.” The martyrs, too, those who have secured the only real triumph, are represented among the blessed carrying palms in their hands (Apoc. vii. 9).

Nor was the bearing of palms confined to religious triumph. The palm is the recognized symbol of victory throughout the world, as the olive branch is of peace. Philo relates that Agrippa carried palms and flowers on his entry into Jerusalem; and Josephus tells the same of Alexander the Great.

Nor was the bearing of palms confined to religious triumph. The palm is the recognized symbol of victory throughout the world, as the olive branch is of peace. Philo relates that Agrippa carried palms and flowers on his entry into Jerusalem; and Josephus tells the same of Alexander the Great.

The palm is admirably adapted to symbolize. It is one of the most useful of Oriental trees. its foliage forms a delightful shade in those hot countries; it supplies dates, a delicious and useful fruit, and a species of wine exudes from its bark. It is thus emblematic of the overshadowing protection of Divine Providence, the strength of supernatural grace, and the nourishment which Our Savior gives us in the Holy Eucharist.

Great variety of opinion exists with regard to the date of the introduction of the blessing of palms into the ceremonial of the Church, and it is impossible to fix it with precision. The custom is admitted, however, to be of ancient origin. Martene, a reliable authority on such matters, asserts that no vestige of the ceremony of blessing palms can be found before the eighth or ninth century; and a Roman Ordo of the eighth century, edited by Frotone, would appear to confirm this opinion; for, treating of the ceremony of Palm Sunday, it makes no mention of the blessing of palms. There is however much that is positive on the other side. Meratus, a consultor of the Sacred Congregation of Rites, produces a number of solid arguments which go to prove the antiquity of this rite. Among these is a calendar of the close of the fourth or the beginning of the fifth century, edited by Martene himself, in which occur the words, “Palm Sunday at St. John Latern” – “Dominica in Palmis de Passione Domini.” Also in the “Sacramentary” of St. Gregory the Great, who occupied the chair of Peter at the close of the sixth century, mention is made of the faithful who were present at Mass with leaves and palm branches in their hands. Venerable Bede (born 672) is the first writer of the West who speaks of palms; but he is immediately followed by St. Aldhelm, Bishop of West Saxony (d. 709), who also makes mention of them.

The custom of blessing and carrying palms in procession appears to have had it origin in the East. And this is but natural; for the in the Old Law it was in the East, as we have seen,![palm[1]](http://www.magnificatmedia.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/palm1.jpg) that God commanded them to be carried; it was in the same region that they were borne before Our Lord; and it was to be expected that those with whom these traditions were local should be the first to imitate them. Most probably the idea of the procession preceded that of the blessing; and the latter was introduced on the general principle that whatever is used by the people of God in His service should first be sanctified by the blessing of the Church. The importance of the event which the procession commemorated would naturally lead to a solemn form for the blessing of the palms to be carried in it.

that God commanded them to be carried; it was in the same region that they were borne before Our Lord; and it was to be expected that those with whom these traditions were local should be the first to imitate them. Most probably the idea of the procession preceded that of the blessing; and the latter was introduced on the general principle that whatever is used by the people of God in His service should first be sanctified by the blessing of the Church. The importance of the event which the procession commemorated would naturally lead to a solemn form for the blessing of the palms to be carried in it.

It must be remarked in passing that Palm Sunday corresponds to the tenth day of the moon, on which the Jews were commanded to select and set apart the lamb without blemish, that was to be eaten on the feast of the Passover.

According to the rubrics of the Missal, the palms presented to be blessed must be the branches of the palm or olive, or other trees. And, although it is not expressly stated, it seems proper that the “other trees” taken in place of the palm or olive, where it cannot be  had, should be some sort of evergreens; at least this is the interpretation put upon the words by the universal practice of the faithful. A decree of the Sacred Congregation of Rites, of June 9, 1668, requires that blessing of the palms to be performed by the priest who is to celebrate the Mass that follows the procession. Commenting on the prayers recited in the blessing of palms, Cardinal Wiseman remarks: “Of the prayers employed in this benediction I shall say nothing but what may be said of all that occur in the Church offices – that they possess an elevation of sentiment, a beauty of allusion, a force of expression, and a depth of feeling which no modern from of supplication ever exhibits.” It is believed that no one who attentively studies these prayers will regard the words of the learned Cardinal as an exaggeration. In the act of blessing the palms the celebrant – vested in violet cope, and standing at the Epistle corner of the altar – after the recitation of a short prayer, continues with the reading of a lesson from the Book of Exodus, in which mention is made of the children of Israel coming to Elim near Mount Sinai, on their journey to the Promised Land, where there were a fountain and seventy palm trees.

had, should be some sort of evergreens; at least this is the interpretation put upon the words by the universal practice of the faithful. A decree of the Sacred Congregation of Rites, of June 9, 1668, requires that blessing of the palms to be performed by the priest who is to celebrate the Mass that follows the procession. Commenting on the prayers recited in the blessing of palms, Cardinal Wiseman remarks: “Of the prayers employed in this benediction I shall say nothing but what may be said of all that occur in the Church offices – that they possess an elevation of sentiment, a beauty of allusion, a force of expression, and a depth of feeling which no modern from of supplication ever exhibits.” It is believed that no one who attentively studies these prayers will regard the words of the learned Cardinal as an exaggeration. In the act of blessing the palms the celebrant – vested in violet cope, and standing at the Epistle corner of the altar – after the recitation of a short prayer, continues with the reading of a lesson from the Book of Exodus, in which mention is made of the children of Israel coming to Elim near Mount Sinai, on their journey to the Promised Land, where there were a fountain and seventy palm trees.

Next in the blessing follows a prayer begging of God that we may in the end go forth to meet Christ, bearing the palm of victory and laden with good works, and so may enter with Him into eternal happiness. Then follow a beautiful preface and five prayers, all invoking  a blessing on the palms, and beseeching God that they may be sanctified, and may become a means of grace and divine protection, both for soul and body, to those who carry them to their homes and keep them there in a spirit of faith and devotion. According to the directions of the ceremonial, the palms should be distributed at the communion rail, those receiving them kissing first the palm and then the hand of the celebrant. The palms are to be held in the hand during the singing or reading of the Passion and the Gospel.

a blessing on the palms, and beseeching God that they may be sanctified, and may become a means of grace and divine protection, both for soul and body, to those who carry them to their homes and keep them there in a spirit of faith and devotion. According to the directions of the ceremonial, the palms should be distributed at the communion rail, those receiving them kissing first the palm and then the hand of the celebrant. The palms are to be held in the hand during the singing or reading of the Passion and the Gospel.

A concluding remark is, however, to be made. The palm is the symbol of victory; but our divine Redeemer, who gained the greatest of all victories, did so by humbling Himself to death, even the death of the cross, to teach us that all true victories are those won by triumphing over ourselves, with our unruly passions and evil inclinations. The palm is made to teach us this salutary lesson among others; for whatever remains after the distribution is laid aside to be burned for the ashes used on the next Ash-Wednesday. These ashes, after having been blessed with solemn prayers, as we have seen, are used to mark the sign of the cross on our foreheads, the seat of that pride infused into our nature by the arch-enemy of mankind at the time of the fall of our first parents. This solemn ceremony is accompanied with the words: “Remember, man, that thou art dust, and unto dust thou shalt return.” It is only by returning to dust, the doom of all the children of Adam, that we can hope to rise to a new life like our divine Model, to die no more, but to bear to His eternal hom and ours the palm of our final victory.

To learn more about Palm Sunday, listen to Learning about the Roman Liturgy today, March 17th, 2016, with Louis Tofari on Magnificat Radio at www.magnificatmedia.com at 10am, 1pm, 6:30pm, and 10pm, CST, USA. Click LISTEN LIVE button. To purchase books and materials mentioned on Learning about the Roman Liturgy with Louis Tofari visit this link: Romanitas Press